Bitcoin's Possibilities for your Grandchildren

The road to economic hell was paved in Keynesian intentions.

A Tired Woman's Epitaph

Here lies a poor woman who always was tired,

for she lived in a house where help wasn’t hired.

Her last words on earth were: "Dear friends, I am going

Where washing ain't done, nor sweeping, nor sewing,

And everything there will be just to my wishes;

For where they don't eat, there's no washing of dishes.

I’ll be where loud anthems will always be ringing,

But having no voice, I’ll get clear of the singing.

Don't mourn for me now; don't mourn for me never,

For I'm going to do nothing for ever and ever.

—Author Unknown

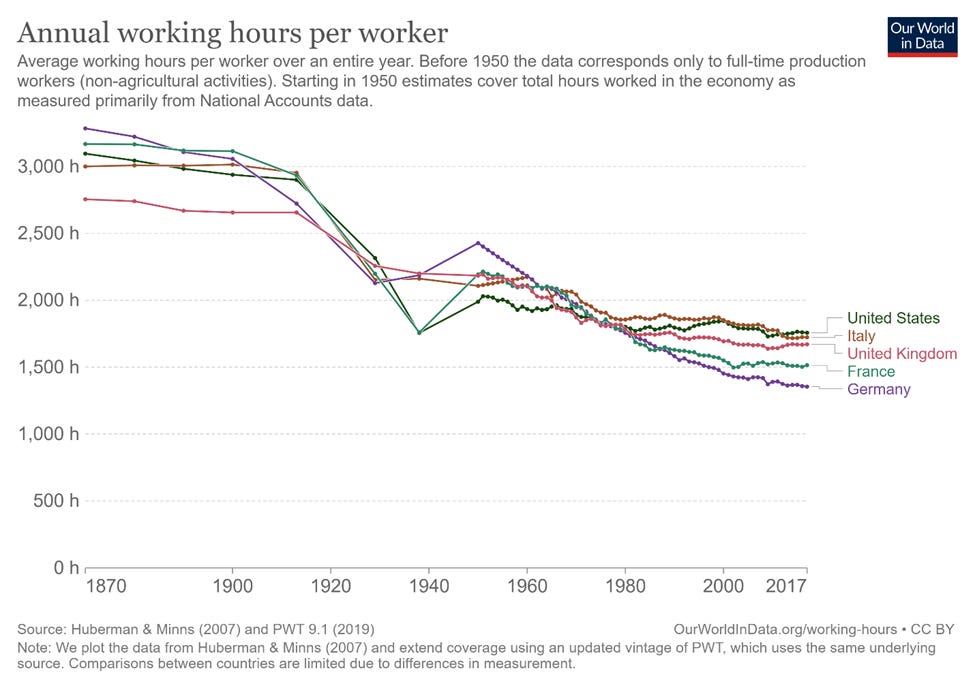

Keynes’ 15 Hour Workweek Prediction

John Maynard Keynes, the early 20th century economist responsible for the Keynesian economics of modern money printing and central planning and the bane of Bitcoiners the world o’er, cited the above poem in his 1930 essay, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren. In the essay Keynes describes the deflationary effects of technology, though he never calls it by that name. He also makes a prediction that in 100 years’ time, by 2030, the average workweek would be 15 hours – and only that much because people would need to be kept occupied with some form of work to feel content. He felt that 3 hours a day, 5 days a week should do the trick for most people.

“Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!”

—John Maynard Keynes, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren

In Keynes’ essay, he estimates that the standard of living in Europe and the United States had increased fourfold thanks to technological improvements in mining, manufacturing and transportation.

Keynes’ prediction roughly played out until the 1970s, when the declining workweek for the world’s largest economies slowed dramatically before basically flatlining. Was Keynes’ wrong? Do people actually want to work 35-40 hours a week (the current average) and not just 15?

Not according to a PEW Research survey conducted in 2021. According to that survey, 39% of workers who quit their job, did so at least in part because they were working too many hours. Clearly a substantial portion of people would like to work less than they currently do. So why has the workweek remained at its current levels rather than continuing the rapid decline of the first two-thirds of the 20th century?

Why the Prediction Has Failed to Materialize

According to the Economic Policy Institute, between 1979 and 2020 worker compensation has risen only 117% despite productivity rising over 164%. Why the disparity? According to the Institute, “Starting in the late 1970s policymakers began dismantling all the policy bulwarks helping to ensure that typical workers’ wages grew with productivity.” What policies were dismantled? The first one listed is that “excess unemployment was tolerated to keep any chance of inflation in check.”

What connection does unemployment have with inflation? Well, Keynesian economics states that inflation and unemployment are inversely correlated. That is, inflation rises as unemployment falls. In order to reduce inflation you must suppress demand, and that means having a higher unemployment rate. This relationship can be graphed in what’s called a Phillips Curve.

Has the Phillips Curve held up through recent history? No, it hasn’t. There are many examples of times when both unemployment and inflation rose together (known as stagflation) which Keynesian economics postulates shouldn’t happen. According to the article, The Phillips curve in the Keynesian perspective:

“When policymakers tried to exploit the tradeoff between inflation and unemployment, the result was an increase in both inflation and unemployment… The US economy experienced this pattern in the deep recession from 1973 to 1975 and again in back-to-back recessions from 1980 to 1982. Many nations around the world saw similar increases in unemployment and inflation.”

Keynesian economists try and write off this contradiction by saying that the Phillips Curve still held, it just “shifted” during these times. However, looking at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ chart of inflation versus unemployment, all you see is a “blob” (as the Associate Professor of Economics Dr. Jonathan Newman put it). There’s no “Curve” to be found.

Central banks are suppressing demand to increase unemployment in the belief that it will reduce inflation. That has added to the stagnation of wage growth despite increased productivity. Meanwhile, inflation has continued to erode the value of the dollar.

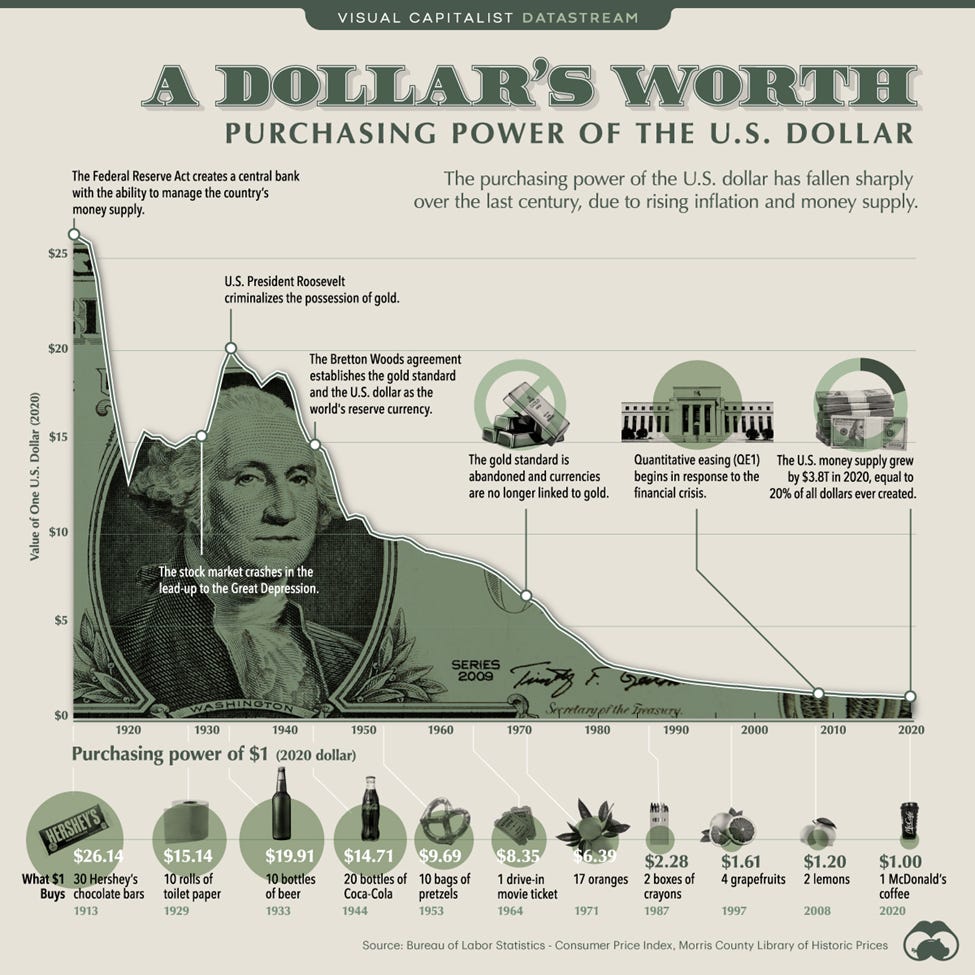

In 1913, one US dollar would buy 30 Hershey’s chocolate bars. According to my local Walmart, today I can buy one Hershey bar for $1.14. In 1933, one US dollar would buy 10 bottles of beer. Today I can get a 6 pack of Miller Lite from Target for $9 ($1.50 per bottle). In 1997, 4 grapefruits cost $1.61. Today my local Walmart sells them for $1.18 each.

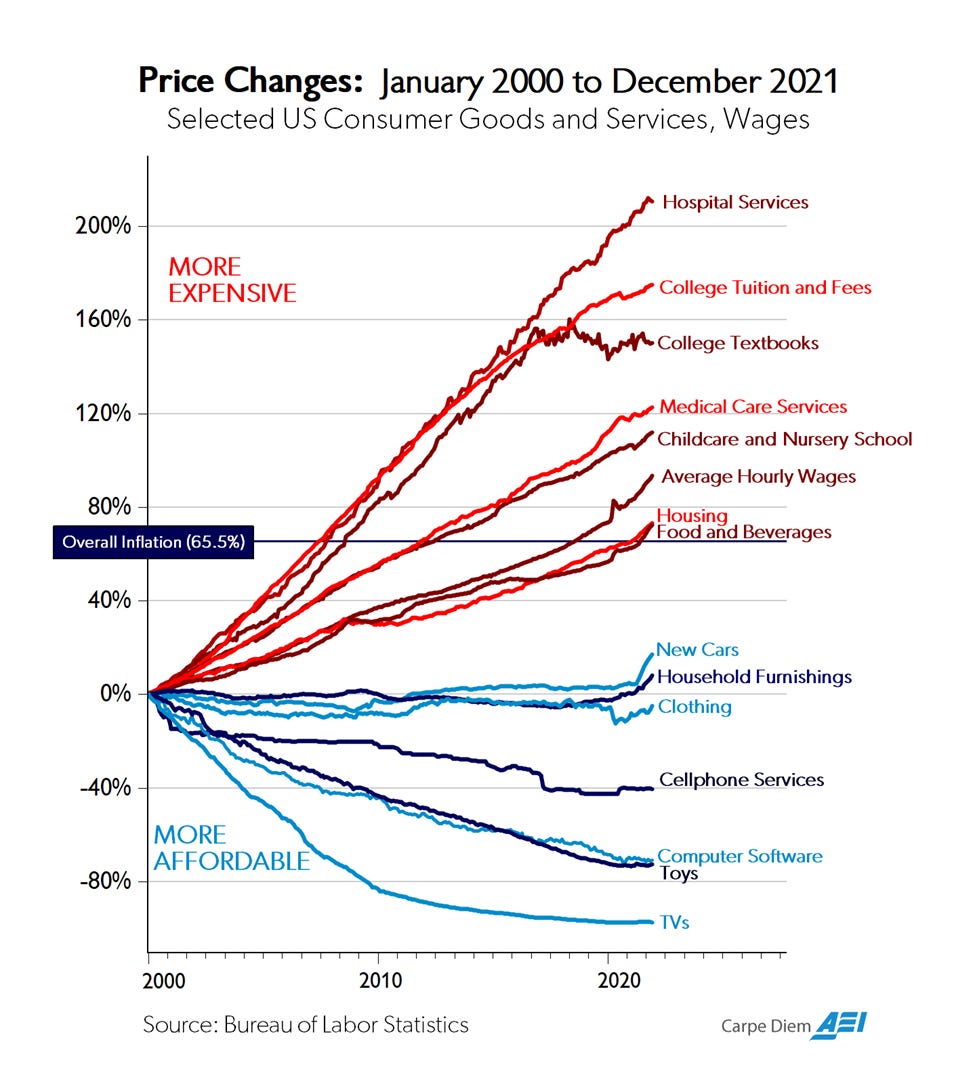

Prices have continued to rise dramatically, which wouldn’t be such a problem if wages had kept pace with that inflation — but they haven’t. Even though many people would like to work less, they can’t afford to do so.

Forced unemployment by central banks isn’t the only thing responsible for rising inflation, however.

Money Printer Goes Brrrrrr

“The "M2 Money Supply", also referred to as "M2 Money Stock", is a measure for the amount of currency in circulation. M2 includes M1 (physical cash and checkable deposits) as well as "less liquid money", such as saving bank accounts. The chart above plots the yearly M2 Growth Rate and the Inflation Rate, which is defined as the yearly change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). When inflation is high, prices for goods and services rise and thus the purchasing power per unit of currency decreases… According to Bannister and Forward (2002, page 28), Money supply growth and inflation are inexorably linked.”

Growth in the money supply causes inflation. It’s basic supply and demand. The more money that gets printed, the less each individual dollar is worth. Keynesian economics states that printing money strengthens the economy because it creates economic activity. As noted in a Forbes article written by Professor of Economics Jeffrey Dorfman, “Keynesians who believe that more spending would cure all our economic woes should support the legalization of counterfeiting.” If all it takes is more money in the system, we wouldn’t have the inflation problems we have now.

In an interview with Jeff Booth on the What Bitcoin Did podcast, Booth, global technology entrepreneur and author of The Price of Tomorrow, states that the supply chain efficiency of producing coffee beans has increased eightyfold since 1980. He then asks, “Why has the price of coffee gone up from 25 cents to four dollars?” Good question.

Keynes’ was correct in his assertion that the technology of his day had increased productivity and the standard of living. Technology is deflationary. This can be seen in the price of things like computers and televisions over time. However, even though, as Booth points out, the efficiency of other supply chains has also greatly increased, the prices of those items have only risen, not fallen. Why?

In Keynes’ time those nations were all on some form of sound money standard, for one. Today those nations are on a fiat standard, with the US dollar as the world reserve currency no longer backed by gold as of 1971. That coupled with Keynesian economics and the rampant inflation produced by the ever-growing money supply explains why prices keep rising rather than falling for almost everything outside of electronics. More money is chasing the same amount of goods and services. Supply and demand.

The Irony

The irony that Keynes’ is actually responsible for preventing his own prophecy’s fulfillment of a 15 hour workweek is as cruel as it is exasperating. His belief that governments could spend their way out of recession and tax their way out of inflation fails to account for human nature.

Brady Swenson of Swan Bitcoin sums up the issue very well in his article How Bitcoin Challenges Keynesian Economics:

“The problem is that it is all too easy for central banks and governments to lower interest rates, print money and spend it in the face of a recession as it is usually a popular thing to do in the short run, but the counter-cycle actions prescribed by Keynes, to raise interest rates and taxes when the economy is growing, are less popular and often never happen.”

Politicians that want to stay in office won’t get reelected if they raise taxes, but they might if they keep handing out “free money” and lowering them. The incentives are all on the side of inflation. So even if Keynes was correct in theory, in practice his economic theory just doesn’t work.

What Keynes Got Right

All that said, Keynes says a number of things in the Economic Possibilities essay that make sense. His belief in the deflationary effects of technology and the benefits it did (and should have continued to) reap were correct. I also agree with his thoughts on people needing meaningful work for fulfillment. It’s not enough to just idle about as he observed the wealthy of his day doing with no good outcomes.

He also discusses people’s instinctual drive to solve the economic problem, “the struggle for subsistence,” and how that drive pushes us to constantly acquire more and to revere the wealthy. He hoped, however, that as the deflationary effect made that drive less necessary, humanity would change.

“The love of money as a possession—as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life—will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semicriminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease.”

—John Maynard Keynes, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren

Bitcoin Fixes This

Whatever Keynes’ intentions were, his economic theory is responsible for paving the road to our current economic hell. We don’t have to continue on that path, however. Bitcoin fixes this. It does so by being distinct from fiat in a number of important ways.

Bitcoin cannot be created out of thin air. It has to be mined, and at great expense and difficulty through its Proof of Work mechanism. That removes the temptation inherent with fiat that can be inflated on a whim by any government desiring to tax its citizens without their consent. That’s what inflation is, after all: unlegislated taxation. It’s theft.

Bitcoin has a fixed supply. There will never be more than 21 million whole “coins”, which ensures the value of each coin continues to rise with its adoption. Each Bitcoin can be broken down into 100 million “satoshis” (sats), allowing for much smaller denominations even as its price inevitably skyrockets. This deflationary effect is good for everyone who adopts it.

Bitcoin is decentralized. There is no individual or group or government that can unilaterally make changes to Bitcoin’s monetary policy. In order to change anything about Bitcoin, a wide consensus must be reached across a diverse geopolitical cross-section of Bitcoin miners and node operators. If you can’t get enough of them to agree to your desired changes, it won’t be implemented. If the changes you want favor you over everyone else, there’s no incentive for them to agree.

Bitcoin is verifiable. Unlike the “trust me bro” attitude of the government when it comes to how your taxes are spent, you can run your own Bitcoin node and see first hand every transaction that’s ever been made. Thus the Bitcoin mantra, “Don’t trust, verify.” Governments in charge of the purse strings have never shown themselves to be trustworthy, so it’s best if we don’t have to trust them at all.

There are many other ways in which Bitcoin is far superior to fiat. For an in-depth education that’s both informative and entertaining, I recommend Saifedean Ammous’ landmark book, The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking. For a brief(er) introduction, I recommend The Bullish Case for Bitcoin by Vijay Boyapati.

The Way Forward

The Great Fiat Experiment is rapidly coming to an end after proving to be an utter failure for the common person (though it has enriched the wealthy to extremes unseen in times past). Governmental debt levels from money printing have reached epic proportions. The global debt spiral has begun, and there’s no stopping it now. The end is nigh.

Rather than building more decks on the Titanic as it sinks, it’s time to abandon ship. But you don’t need to swim in those cold economic waters to get ashore. Bitcoin is the lifeboat; for you, your children, your grandchildren and all of humanity, even 100 years from now.